A LIFE IN CONTRAST

Documenting a Legacy with Director Ondi Timoner

~ by joel martens ~

To say Robert Mapplethorpe was provocative is an understatement. Great cutting-edge artists often are, because they challenge social norms.

For those of us who remember his work, early career, and the surrounding controversies around his photography, that reality isn’t far off the mark. His exhibition, The Perfect Moment at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center, pushed the boundaries of what was considered “decent.” It essentially put the art world on trial in a highly publicized and political showdown that threatened the very foundations of free speech and how the arts were funded.

The show and its reaction were representative of much that was happening in society around sexuality, freedom of speech, LGBTQ rights, women’s rights and the changing social norms of the times. HIV/AIDS had taken a devastating toll and morality was as a bludgeon used to try and silence the LGBTQ community and to cripple the change that was occurring.

As it often is, art was one of the ways protest occurred and the more controversial, the better. Interestingly enough, the morality trial that sought to destroy him essentially cemented Robert Mapplethorpe’s legacy. And, the show that fueled it was timely, especially when considering Mapplethorpe died of complications from AIDS just a few months earlier, posthumously raising interest in his body of work.

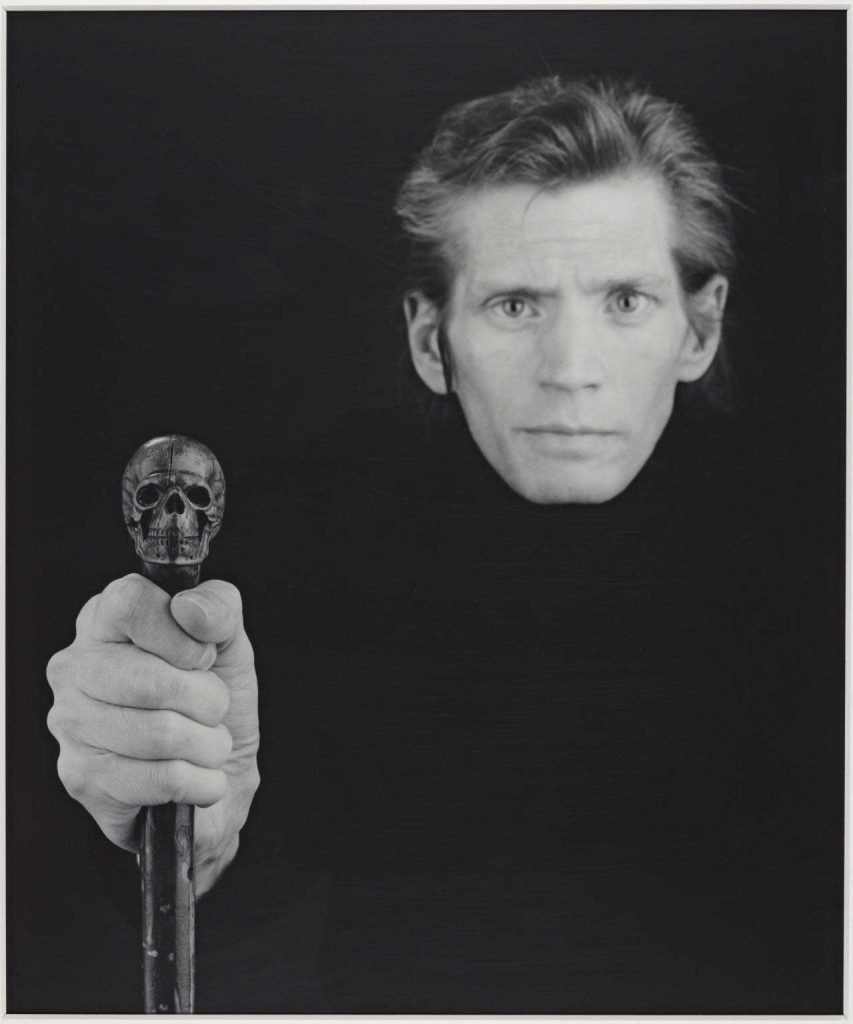

Mapplethorpe rose to prominence because of his stunning depictions of life in 1970s New York, through his highly contrasted black-and-white photography. Work that included famous celebrities, floral still lifes, unflinching nudes (including images of gay men) and graphic depictions of sadomasochism. Undeniably beautiful and undeniably raw, his art is a study in contrasts—light and dark, moral and immoral, power and submission—pushing the edge of what art could be. He literally brought life hidden, out of the shadows and illuminated them so the world could see the beauty there… challenging them to look beyond stereotypes.

Ondi Timoner, the American film director, producer, editor, as well as founder and CEO of Interloper Films, understood Robert Mapplethorpe to be the trailblazer he was and wanted to illustrate his life on film. The only two-time recipient of Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize for documentaries (DIG! and We Live In Public), she is known for her unflinching, socio-political documentaries on subjects ranging from the music business and the U.S. prison system to religious cults and climate change.

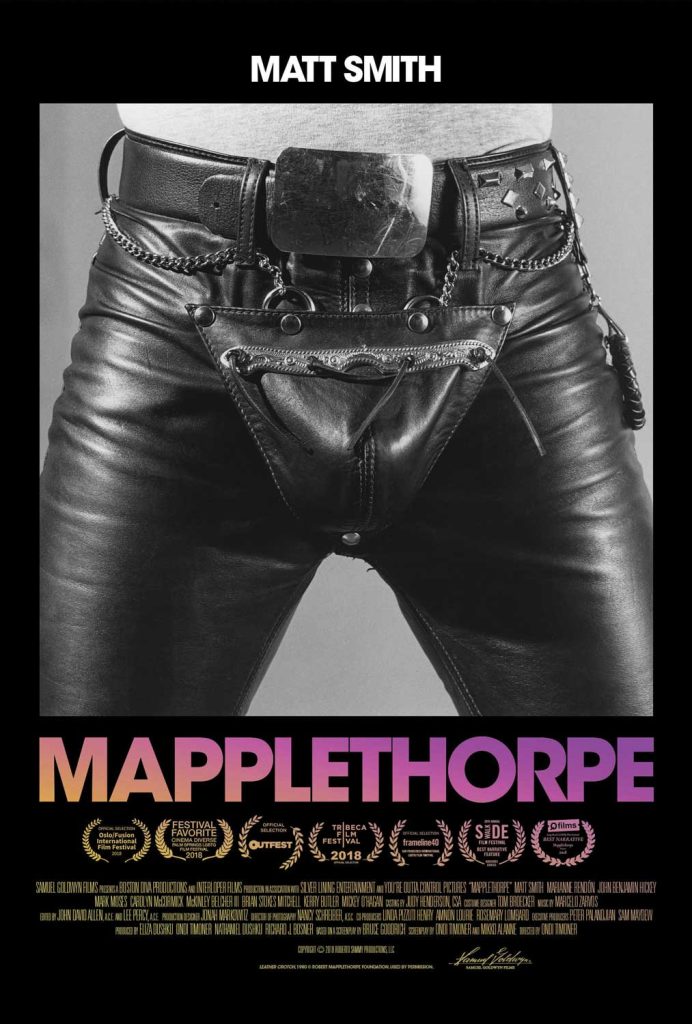

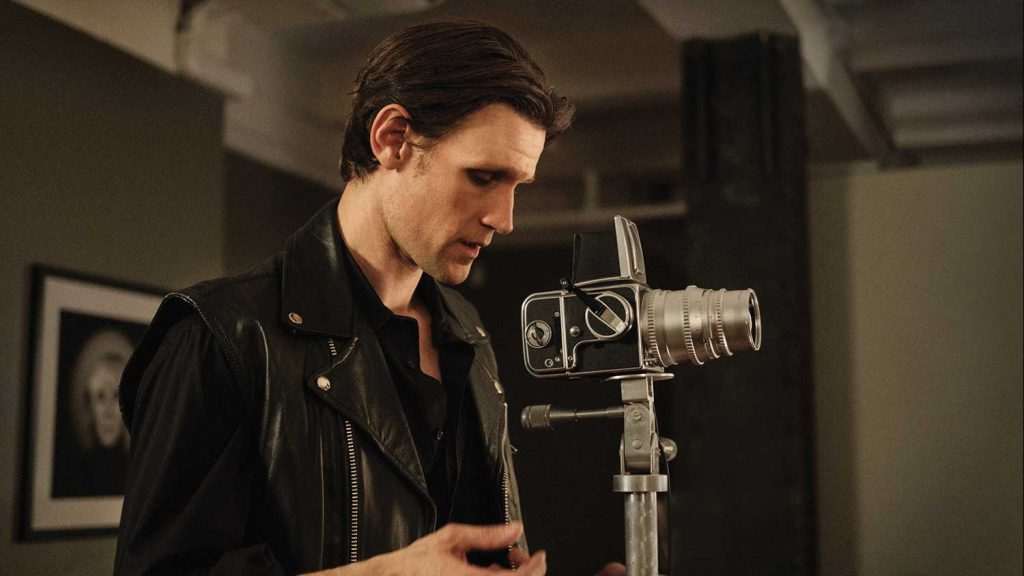

Timoner was passionate about making Mapplethorpe happen and spent seven years writing and developing the film, then unbelievably, only 19 days shooting it. The Crown’s Matt Smith plays the creative genius, from his early days with only a Polaroid camera, up until his death in 1989.

Timoner sat down with The Rage Monthly for an in-depth conversation about Mapplethorpe the man and Mapplethorpe the film.

It was interesting researching you, because there’s sort of a theme that runs through your work: people who live outside the rule books be it good or bad, in lightness or dark. It’s a fascinating perspective on humanity. Is that something you’ve always chased or is it a sensibility you came into?

Yes, impossible visionaries… and it’s a combo. I think my stories are very different, but there is this running theme to some extent. These subjects have come to me and now it’s like a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I was raised by an entrepreneur, a maverick personality. My father redefined the way air travel happened in America. He had the fastest airline in the history of America at that point in history. He had a tragic accident and ended up having a massive stroke when he was 52 and I was nine. He lost the airline and everything I knew… My next screenplay is about this, actually.

Watching him take the risks that he took in the first ten years of my life and even after that, and watching my mother support him—they raised me to be a risk taker—to kind of just “go for it.” The idea that there was nothing I couldn’t do, or that I shouldn’t and to just try. I feel like those people, the kind who draw the lines and push the edges, those are the people who are defining what our society looks like and where we’re going.

They can see things we can’t just yet see and don’t understand and they have to withstand the doubt and ridicule of people around them in order to stick to their vision. Robert Mapplethorpe is one of those people. He was operating at a time when what he was photographing was deemed obscene and he had to withstand a lot of criticism and a lot of rejection. He was absolutely underground, but was determined his work should be on the gallery floor and that it should be collectible. He believed we should see beauty in form and in pure sculptural form; even in those things often relegated to the underworld.

He was vilified by the moral majority and so many in the press during those early shows. I vividly remember how vicious it was.

Yes. I wanted to bring him alive on screen and really make Mapplethorpe an anthem for artists. I wanted people to see and think “I can do that too, even if I have fatal flaws.” That’s why Matt [Smith] and I decided to make such an unflinching portrait of him. To make sure people don’t feel just because they are “this way or that,” they can’t do incredible things and that their vision shouldn’t be made real. That is my goal with telling these stories; to tell them with a lot of grey area and not clean people up too much.

It was fascinating to watch you recreate his photo shoots. It offered an interesting perspective around seeing the world through his eyes as an artist. He’s a complex man in some ways and yet so simple in others. His Catholic upbringing and the relationship he had with his father, I think it forced him to think outside of the box. He was always chasing something because of it, I think pretty much his whole life. Do you feel that’s true?

He was always chasing. That was what I saw in Matt, too and that made me cast him. He just had this underlying tension. He’s never satisfied and nothing was ever perfect enough. He is mercurial, there was a bubbling going on underneath the surface and that was the character I was writing with Mapplethorpe. I reflected in a way how Robert Mapplethorpe destroyed his intimate relationships because they were imperfect. They could be fallible at a certain point and he was always driving toward perfection… always.

You shot this film on eight and 16-millimeter film, was that because you were trying to be respectful of the time frame and material he used? What fueled that choice?

Actually, the person that fueled that choice was the president or Kodak, Steve Bellamy. He said that I would be committing a crime against humanity to tell Robert Mapplethorpe’s story on anything but celluloid. I told him, “If that’s true then you need to make it possible. If you feel that way, then you need to facilitate us doing that.” He took the challenge and made it happen for us. We shot the movie in 19 days and he made it possible according to our budget and timeframe.

Cultural icons like Mapplethorpe come into the world and they don’t necessarily receive acclaim right off the bat. They are doing so much more than just creating art. It’s the conversation around what they are creating that becomes important, and Robert Mapplethorpe did that for sure. I appreciated the fact that you tell the story within the context of what was happening as far as the AIDS crisis. There was a war going on and it became personal because Mapplethorpe was sick. How difficult was it to make his homosexuality and what was going on culturally, fit the context of his art into the story?

I thought the moment where he is photographing David Croland in that sort of the pre-coital moment, it’s like sort of a foreplay build up photo shoot and Croland said, “You know we should go down to Stonewall, that’s where the revolution is.” Mapplethorpe’s response was, “The revolution is in my camera.” I think he saw what he was doing and knew what was going to happen if he succeeded, that the walls were gonna come down. He had no idea the controversy that it would stir around the time of his death and posthumously… It all happened just at the perfect moment.

The original script that I optioned in 2000, looked at it from the perspective in the courtroom and the decency trial that occurred and looking back on that. I wanted to make an unfolding story in which Robert was a real person, over time in the context of history. Who he is in relation to that period of time was really, really important. The fact that he and Sam Wagstaff in combination made photography a collectible art form, for example. That’s why there’s a montage with Pac Man and Ronald Reagan, to put a kind of historical context to it all. A few touchstones so that you can recognize just how revolutionary his art was.

It’s interesting, the Guggenheim has a retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s work currently, Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now. The photographs on display there are not controversial anymore, even with the current tensions right now. They’re simply gorgeous and not shocking in any way.

One of the most powerful moments in the film for me was that moment with Sam Wagstaff when he was talking about the “gallery of the dead.”

I couldn’t tell his story without both the story of his aging, his coming into his sexuality and in turn coming into his art. To peel back the layers of his psyche, which made him realize that he’d be unable to turn away from his sexuality. I couldn’t tell the story without that and then also without the AIDS crisis… there was no way

I saw it as a triptych in a way: Mapplethorpe’s coming of age story and his coming into his art. Then his fighting like hell to be recognized in the ‘70s, then discovering Sam and then his death just as he had achieved all that he had ever dreamt of.

It’s fascinating, all the light and darkness in Mapplethorpe’s life is reflected in all aspects of his work: Damnation versus salvation, the light and darkness and the opposition of those things.

Yes, yes, yes. That’s why the photography is the way it is, it’s funny you picked up on that. I knew that the film would fail if we didn’t make it as beautiful as his work. Not to say that the film is as beautiful as his work, but it at least had to live up to it, visually. The work that Nancy [Schreiber, the cinematographer] did, I pushed her and almost made her insane. (Laughs) But, the lighting was so important and everything had to be backlit, it had to be silhouetted and side lit, it had to have light and dark in it or it’s just not going to work. That was Mapplethorpe, light and dark, that contrast was everything.

Even with his more blatantly sexual imagery, they are so beautiful because of the lighting and his ability to see the sculptural form in everything. So much of that was lost at the time because it was controversial, but it was undeniably beautiful.

When I was rewriting the script after the Sundance lab in 2010, basically from page one, the Mapplethorpe Foundation sent a bunch of books to me. There were two that were really crucial to me, one of them comparing his work to Auguste Rodin and the other to Michelangelo. That made me realize what he is trying to do. Mapplethorpe was trying to turn his work into undeniable sculptural forms so people can’t say, “Oh that’s just riff-raff.” He refined his eye and realized, “Oh, I can turn this into a gorgeous studio work, by making it like a bust.” So, at the beginning of the film, when he’s in the pool and he’s documenting the people with a Polaroid, that’s the beginning of the beginning. He’s like a verité documentary filmmaker holding onto a tiger’s tail that led him into worlds he could never otherwise enter.

One of the things I think is really important about films like this, especially from that time period, is it documents those cultural icons in the LGBTQ community. So many of them died during the AIDS crisis and we need those stories because otherwise that history is lost. It is such an important legacy to pass on, those early trailblazers who fought and literally allowed us to become who we are today.

I wanted to inspire artists and really just step out of line and continue to do interesting things to break the rules and inspire people to make their art. I want people to know, that even if they have fatal flaws like Robert Mapplethorpe did, that they can still do incredible things.

It’s the 30th anniversary of his death and I was inspired to tell his story because I felt like someone like Mapplethorpe should be brought alive and it’s been a real privilege.

Mapplethorpe opened on Friday, March 1, check your local listings for times and places. For more information or to see a trailer, go to samuelgoldwynfilms.com/Mapplethorpe.